Only three types of platforms were targeted: Joomla ( /administrator/index.php), WordPress ( /wp-login.php), and Datalife Engine ( /admin.php). For an interactive map showing infected clients, click here.Ĭontinuing to analyze the logs recovered from the C&C, we were able to compile a list of usernames and passwords for 6,127 sites. Interestingly, it seems the United States and Western Europe are underrepresented. The top three countries with infections are the Philippines, Peru, and Mexico. Mitigating factors such as double-counting infections behind a NAT, and infected machines changing IP addresses may affect the final tally. We found 25,611 unique IP addresses connecting to the six C&C sites. Some level of skepticism is required, since we are analyzing data that could have been altered by the attacker. The log files found on the C&C sites included the IP addresses of victims. The C&C sites did not offer additional clues as to the infection mechanism. It’s unclear if victims were enticed to run these files, and if so, if that is the only means of infection.

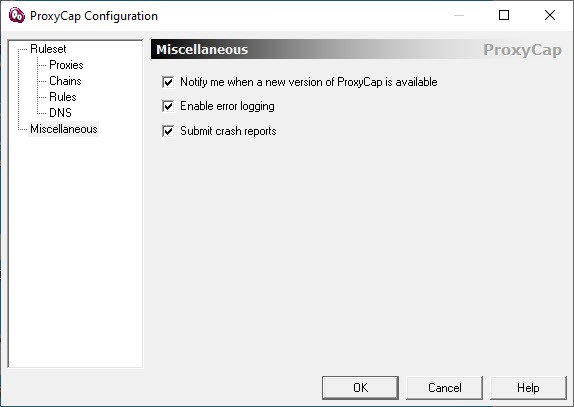

#PROXYCAP FLAWS CRACK#

Another filename, proxycap_crack.exe, refers to a crack for the Prox圜ap program. We were able to find reference to the malware’s original filename ( maykl_lyuis_bolshaya_igra_na_ponizhenie.exe) that referred to Michael Lewis’ book “The Big Short: Inside The Doomsday Machine” in Russian with an executable attachment. It’s unclear exactly how the malware gets installed. Results are appended to a text file publicly accessible via the web. Successful username/password combinations are reported back to the C&C by posting to the file /bruteres.php.

The malware will attempt to login to the target list with combinations of the supplied usernames and passwords. What's particularly interesting about this bruteforce list is that it supports the dynamic values values.

#PROXYCAP FLAWS PASSWORD#

The fourth line is the password to use, and in some cases can be a URL to a password list. The C&C tends to give out the same list to multiple infections. We've observed the target list being anywhere from 5,000 to 10,000 sites at a time. The third line is a URL of a list of sites to attack. The command structure can vary, but the important commands are the third and fourth lines. The malware then checks in to receive commands:

A newly infected machine registers with the C&C site hardcoded into the malware:

#PROXYCAP FLAWS WINDOWS#

There are at least four variants of the Windows malware related to the Fort Disco campaign. The sites either share a subdomain or are co-hosted with each other, and have similar structures. There are six C&C sites that we believe are related. The controller of the campaign we call Fort Disco, named after one of the strings found in the PE metadata field, inadvertently left publicly accessible log files that lay out a complete picture of the campaign. In rare instances, the controller of a botnet may inadvertently leave clues publicly accessible for anyone to observe. They can sinkhole discarded domains or monitor traffic to live attack sites to observe infected hosts checking in to a C&C site. Researchers have several techniques at their disposal to gauge the size of a botnet. Several things can be inferred, but painting a complete picture is difficult. It’s much like a historian finding a discarded weapon on an ancient battlefield. The malware alone can be picked apart by disassemblers, poked and prodded in a sandbox, but by itself offers no clues into the size, scope, motivation, and impact of the attack campaign. Understanding an attack campaign by only analyzing a malware executable file is a Sisyphean task. To date, over 6,000 Joomla, WordPress, and Datalife Engine installations have been the victims of password guessing. We’ve identified six related command-and-control (C&C) sites that control a botnet of over 25,000 infected Windows machines. Arbor ASERT has been tracking a campaign we are calling Fort Disco that began in late May 2013 and is continuing. In recent months, several researchers have highlighted an uptick in bruteforce password guessing attacks targeting blogging and content management systems.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)